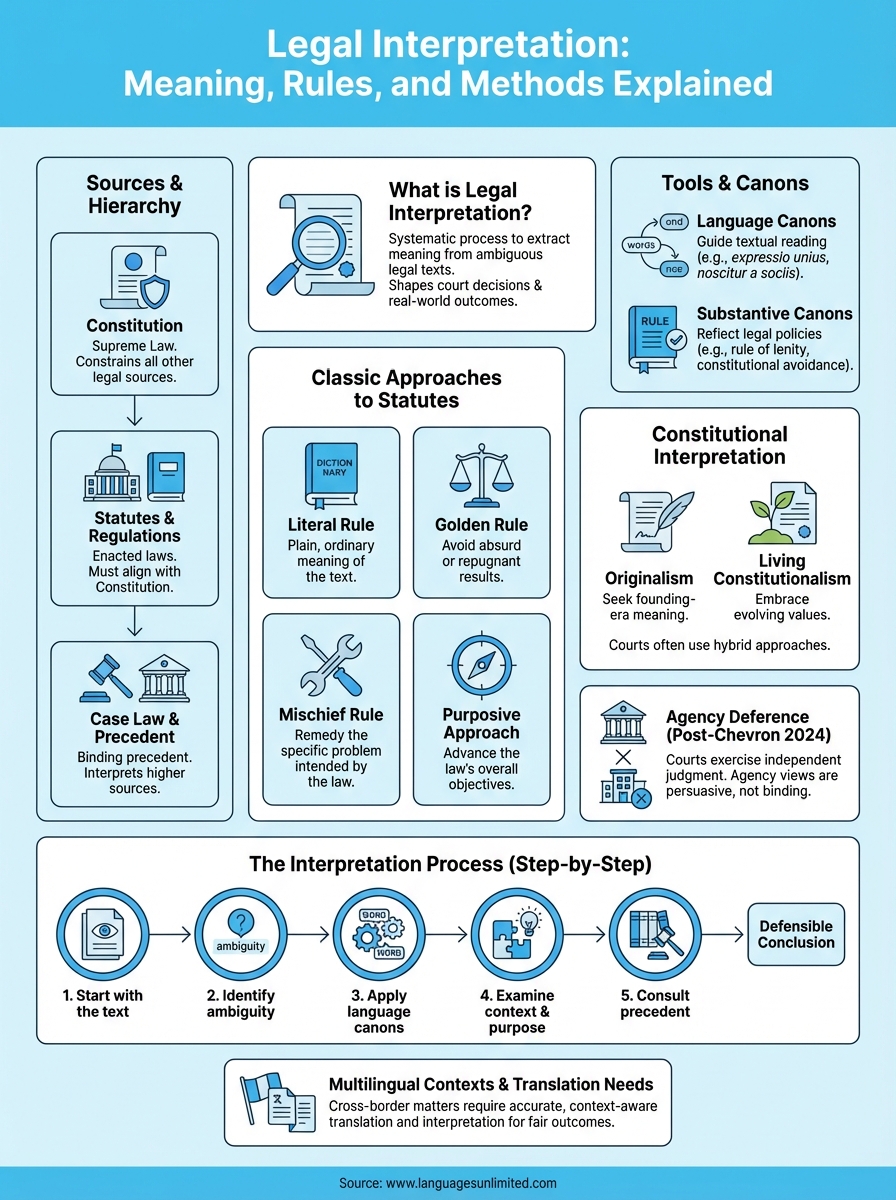

Every contract clause, statutory provision, and constitutional amendment carries weight far beyond its surface text. Legal interpretation is the systematic process through which judges, attorneys, and legal scholars extract meaning from written laws and documents, a discipline that shapes court decisions, influences policy outcomes, and determines rights and obligations for millions. Whether you’re reviewing a contract for cross-border business or navigating immigration proceedings, understanding how legal texts are analyzed provides critical insight into how the law actually functions.

At Languages Unlimited, we’ve spent over three decades helping legal professionals, courts, and government agencies bridge language barriers in high-stakes legal matters. Our certified translators and interpreters work daily with contracts, court documents, and immigration papers where precision isn’t optional, it’s mandatory. This experience has shown us that accurate communication in legal contexts demands more than word-for-word conversion; it requires a deep appreciation for how legal language carries specific, often technical meanings that courts interpret through established rules and doctrines.

This article breaks down the core principles of legal interpretation, from foundational rules like the literal, golden, and mischief approaches to modern purposive methods used by courts today. You’ll learn how judges determine legislative intent, why certain interpretive tools take precedence over others, and how these methodologies apply across different legal systems. Whether you’re a paralegal preparing case materials, an attorney refining arguments, or simply someone who wants to understand how laws are read and applied, this guide provides the clarity you need.

Why legal interpretation matters

Legal interpretation determines real outcomes for people and organizations every day. When a court interprets an ambiguous clause in a merger agreement, billions of dollars can shift between parties. When judges read an immigration statute one way rather than another, families stay together or face separation. The practical stakes extend far beyond academic debates about meaning because interpretation directly shapes who wins lawsuits, which contracts get enforced, and how constitutional rights apply to new situations.

Real consequences in everyday legal disputes

You see interpretation’s impact most clearly in contract disputes. Two parties sign an agreement that seems clear until circumstances change, and suddenly both sides claim the text supports their position. Courts must choose between competing readings, and that choice determines whether a business owes millions in damages or walks away unscathed. Insurance coverage disputes offer another stark example: when a policyholder files a claim, the insurer’s obligation often hinges on how a judge interprets exclusion clauses written in dense legal language. A narrow reading might force payment; a broad reading leaves the claimant without coverage.

Criminal cases raise even higher stakes. Statutory interpretation can mean the difference between freedom and incarceration. When legislators write laws prohibiting certain conduct, they cannot anticipate every future scenario. Courts must decide whether a statute covers new technologies, unforeseen behaviors, or edge cases the drafters never considered. The rule of lenity, which requires ambiguous criminal statutes to be interpreted in favor of defendants, reflects how seriously legal systems treat these interpretive choices when personal liberty hangs in the balance.

The meaning a court assigns to legal text ripples outward, creating precedent that binds future disputes and shapes how millions of people understand their rights and obligations.

Predictability and consistent application across cases

Legal interpretation provides the analytical framework that allows lawyers to advise clients with confidence. When you consult an attorney about whether a proposed action is legal, that attorney applies established interpretive rules to relevant statutes and regulations. Without consistent methodologies, legal advice would devolve into guesswork, and businesses could not plan investments or individuals could not structure their affairs with any certainty about legal consequences.

Courts rely on interpretation to maintain coherence across the legal system. When one judge interprets a statute using textualist principles and another applies purposive analysis to the same provision, litigants in similar cases face radically different outcomes depending on which courtroom they enter. Shared interpretive frameworks, though applied differently by individual judges, create baseline predictability that allows the legal system to function. Lawyers can identify likely outcomes, parties can settle disputes without trial, and society can organize itself around legal rules that mean roughly the same thing from one case to the next.

Cross-border and multilingual legal contexts

International transactions and immigration proceedings add layers of complexity to legal interpretation because they involve texts in multiple languages and legal traditions. When a contract is drafted in English but governs conduct in jurisdictions where parties speak Spanish, Mandarin, or Arabic, questions arise about which version controls and how translation affects meaning. Courts must decide whether to interpret the English text using American legal canons or whether to account for how terms would be understood in the other party’s legal system.

Immigration law demonstrates these challenges daily. Applicants submit documents in dozens of languages that must be accurately translated and then interpreted according to U.S. legal standards. A marriage certificate from the Philippines, a diploma from Ukraine, or a police clearance from India each carries legal significance that depends on both accurate translation and correct interpretation of requirements in U.S. immigration statutes and regulations. The interplay between language and law makes professional interpretation and translation essential to fair outcomes in these proceedings.

What legal interpretation is and is not

Legal interpretation involves applying established methodologies to extract meaning from written legal texts when their application to specific facts is unclear. You engage in interpretation when you analyze statutory language, constitutional provisions, regulations, or contractual terms to determine how they govern a particular situation. This process requires reasoned analysis using recognized tools and canons rather than personal preference or policy desires. Courts, attorneys, and legal professionals perform interpretation as a discipline with boundaries, not as an exercise in creative writing or political advocacy.

What counts as interpretation

Interpretation begins when text creates genuine uncertainty about its application to facts before you. If a statute prohibits "vehicles" in parks and someone brings a motorized wheelchair, you must interpret whether the term "vehicles" includes mobility devices. You apply textual analysis, examine legislative history, consider the statute’s purpose, and consult precedent to reach a defensible conclusion. Ambiguous contract terms present similar challenges: when parties dispute whether "delivery" means physical arrival or when goods leave the warehouse, you interpret by examining context, trade usage, and the parties’ prior dealings.

You also interpret when legal texts conflict or overlap. Constitutional provisions may appear to support contradictory conclusions, statutes from different years may address the same conduct differently, or federal and state laws may create tension. Courts must reconcile these conflicts through interpretation that harmonizes sources where possible or establishes which provision controls. This reconciliation process requires applying constitutional principles, statutory construction rules, and jurisdictional doctrines that determine hierarchy among competing legal texts.

Interpretation fills gaps and resolves ambiguities that drafters could not foresee, but it never rewrites clear text to reach preferred outcomes.

What interpretation does not include

Legal interpretation is not judicial legislation where courts insert their policy preferences into statutes. When statutory text clearly prohibits certain conduct, you cannot interpret your way around that prohibition simply because you believe the law produces unfair results. Courts lack authority to rewrite unambiguous provisions, and attorneys cannot ignore clear language in contracts just because their clients would prefer different terms. The distinction between interpretation and revision marks a fundamental boundary in legal analysis.

You also do not interpret when text clearly answers the question before you. If a statute sets a filing deadline at thirty days and someone files on day thirty-one, no interpretation is needed because the text unambiguously requires dismissal. Similarly, when a contract states payment is due "within ten business days of invoice," you apply that plain language without searching for hidden meanings or alternative readings. Interpretation begins where textual clarity ends, not before.

Where interpretation happens in the legal system

Legal interpretation occurs across multiple institutional settings, each with distinct authority and consequences. You encounter interpretation most visibly in courtrooms, but it also happens when administrative agencies apply regulations, when attorneys draft contracts and advise clients, and when legislators clarify the scope of their own enactments. Understanding where interpretation takes place helps you recognize who has the power to create binding legal meanings and whose interpretations carry persuasive rather than mandatory weight.

Courts at every level

You see interpretation in action at trial courts where judges must apply statutes, regulations, and constitutional provisions to specific disputes between parties. A district court judge interpreting whether a statute of limitations bars a particular claim creates a ruling that binds the parties before her, though other judges remain free to interpret the same statute differently. These trial-level interpretations generate the factual record and initial legal analysis that appellate courts later review.

Appellate courts perform interpretation with greater precedential force because their decisions bind lower courts within the same jurisdiction. When a federal circuit court interprets a provision of the Clean Air Act, every district court in that circuit must follow that interpretation in future cases. State appellate courts similarly create binding interpretations of state statutes and constitutional provisions that trial judges must apply. You rely on these appellate interpretations when researching how courts will likely read ambiguous legal texts.

Supreme courts hold the final word on interpretation within their jurisdiction, creating precedent that all lower courts must follow until the legislature amends the statute or the high court reverses itself.

Administrative agencies and regulatory interpretations

Federal and state agencies regularly interpret statutes and regulations they administer. The Environmental Protection Agency interprets the Clean Water Act, the IRS interprets the Internal Revenue Code, and state labor departments interpret workplace safety laws. These agency interpretations historically received deference from courts under doctrines like Chevron, though recent Supreme Court decisions have narrowed that deference. You still encounter agency interpretations through guidance documents, formal rulings, and adjudicatory decisions that shape how regulated parties understand their obligations.

Legal practice and transactional settings

Attorneys perform legal interpretation whenever they advise clients about contract terms, statutory compliance, or regulatory requirements. You draft agreements with language you interpret to mean specific things, structure transactions based on your reading of tax statutes, and counsel clients about litigation risk by interpreting how courts will likely read disputed provisions. This front-end interpretation prevents disputes, though it lacks binding authority until a court adopts your reading if litigation occurs.

Key sources and the legal hierarchy

Legal interpretation draws from distinct sources that operate within a formal hierarchy determining which texts control when conflicts arise. You must understand this hierarchy to interpret correctly because a statute always trumps a conflicting regulation, and the Constitution overrides both. This vertical ordering shapes how you approach interpretation: when you analyze a legal question, you start at the top of the hierarchy and work downward, applying the highest-ranking source that addresses your issue. Ignoring this structure produces interpretations that courts will reject, no matter how thoughtfully reasoned.

Constitutional provisions as supreme law

The Constitution sits at the apex of the hierarchy in American law, and no statute, regulation, or judicial decision can contradict its provisions. When you interpret any legal text, you must ensure your reading aligns with constitutional requirements. Courts use judicial review to strike down laws that violate constitutional guarantees, making constitutional interpretation the ultimate backstop in legal analysis. You invoke constitutional principles when statutes threaten individual rights or when government action exceeds enumerated powers.

Federal and state constitutions establish the framework within which all other law operates. State constitutions can provide greater protections than the U.S. Constitution but cannot offer less. This relationship means you sometimes interpret state law by reference to both federal constitutional minimums and state constitutional provisions that extend further.

Constitutional text constrains all other legal sources, requiring you to interpret statutes and regulations in ways that avoid constitutional conflicts when possible.

Statutes and regulations below the Constitution

Statutes enacted by legislatures occupy the second tier of the hierarchy, binding everyone within the enacting body’s jurisdiction. Federal statutes control matters within Congress’s constitutional authority, while state statutes govern areas reserved to states. When you interpret regulations, you must ensure they remain consistent with authorizing statutes because agencies cannot exceed the power legislators delegated to them. Regulations fill gaps in statutory schemes but cannot contradict the statutes they implement.

This relationship requires you to interpret regulations narrowly when they appear to expand beyond statutory authority. Courts routinely invalidate regulations that exceed statutory bounds, making it essential to read agency rules in light of their enabling legislation.

Case law and precedent in the hierarchy

Judicial decisions interpret constitutional provisions, statutes, and regulations, creating binding precedent that shapes how you read legal texts in future cases. While case law does not outrank the sources it interprets, precedent establishes the authoritative meaning of ambiguous provisions until legislatures amend statutes or higher courts overrule prior decisions. You rely on precedent to predict how courts will interpret similar language, making case law indispensable to practical legal interpretation despite its subordinate position in the formal hierarchy.

The four classic approaches to statutes

You encounter four fundamental methodologies when interpreting statutes, each offering a distinct framework for extracting meaning from legislative text. These approaches developed over centuries of judicial practice in common law systems, and courts still apply them today, though often in combination rather than isolation. Understanding how each method works equips you to predict judicial reasoning and construct stronger legal arguments. The literal, golden, mischief, and purposive rules represent different philosophies about where meaning resides and what role judges should play in discovering it.

Literal rule focuses on plain text

The literal rule instructs you to give words their ordinary, natural meaning as understood in everyday language unless the text itself defines them differently. You apply this approach by examining dictionary definitions, common usage at the time of enactment, and grammatical structure without reference to legislative intent or policy consequences. When a statute prohibits "vehicles" in parks, the literal interpreter asks only what reasonable English speakers mean by "vehicles," typically concluding that cars, motorcycles, and trucks qualify while bicycles might not.

Courts applying literal interpretation enforce the text even when results seem harsh or unintended, reasoning that legislators chose their words deliberately and judges lack authority to second-guess those choices. This method prioritizes predictability and legislative supremacy over judicial flexibility.

Golden rule prevents absurd results

You apply the golden rule as a modification of literal interpretation that allows departure from plain meaning only when strict adherence produces absurd, inconsistent, or repugnant outcomes. This approach maintains fidelity to text as the starting point but recognizes that legislators cannot anticipate every application. When literal reading would create results no reasonable legislature could have intended, you interpret the statute to avoid that absurdity while staying as close to the text as possible.

Mischief rule targets legislative gaps

The mischief rule directs you to interpret statutes by identifying the specific problem lawmakers intended to remedy. You examine the legal landscape before enactment, determine what "mischief" the legislature sought to address, and read the statute to suppress that mischief and advance the remedy. This approach originated in 16th-century England but remains influential, particularly when interpreting remedial legislation designed to correct identified defects in prior law.

The mischief rule shifts interpretive focus from text alone to the social problem lawmakers meant to solve, making legislative history and context essential to legal interpretation.

Purposive approach pursues statutory goals

Modern purposive interpretation requires you to read statutory language in light of the legislation’s overall purpose and objectives. You identify the goals Parliament or Congress sought to achieve, then interpret individual provisions to advance those aims. This method goes beyond the narrow mischief rule by considering broad policy objectives rather than just remedying specific defects. Courts using purposive interpretation examine legislative history, committee reports, and statutory structure to discern purpose, then apply text in ways that fulfill legislative intent even when plain meaning might frustrate it.

Canons and tools lawyers use

You apply interpretive canons as shorthand rules that guide how you read statutory language when ambiguity appears. These canons represent centuries of accumulated judicial wisdom about how legal texts function, offering predictable pathways through interpretive disputes. Lawyers invoke these tools in briefs, judges cite them in opinions, and legal scholars debate their proper scope and application. Understanding the major canons transforms you from someone who guesses at meaning to someone who constructs reasoned arguments backed by established analytical frameworks that courts recognize and respect.

Language canons guide textual reading

You encounter language canons whenever you analyze how words relate to each other within statutory text. The expressio unius canon tells you that expressing one item excludes others, so when a statute lists "cars, trucks, and motorcycles," you interpret it to exclude bicycles because the legislature specifically enumerated motor vehicles. This principle operates across legal interpretation, helping you determine scope by paying attention to what drafters included and what they left out.

Noscitur a sociis instructs you to interpret words by reference to their companions, so "dogs, cats, and other animals" likely refers to household pets rather than livestock or wildlife. The ejusdem generis canon similarly requires general terms following specific ones to match the same category. When a statute prohibits "firearms, explosives, and other dangerous weapons," you interpret "dangerous weapons" to mean items similar in kind to guns and bombs, not baseball bats or kitchen knives, even though those can cause harm.

Language canons provide systematic tools for extracting meaning from text by examining how words interact with surrounding terms and structural patterns.

Substantive canons reflect legal policies

Substantive canons direct you to prefer interpretations that align with background legal principles rather than neutral textual analysis. The rule of lenity requires you to construe ambiguous criminal statutes in favor of defendants, reflecting the policy that criminal laws must provide clear notice before imposing punishment. You apply this canon only after exhausting other interpretive tools and finding genuine ambiguity that cannot be resolved through textual or purposive methods.

Constitutional avoidance instructs you to choose interpretations that keep statutes within constitutional bounds when text permits multiple readings. Courts prefer saving legislation rather than striking it down, so you interpret ambiguous provisions in ways that avoid serious constitutional questions. The canon protecting state sovereignty similarly guides you to read federal statutes as leaving traditional state powers intact unless Congress clearly intended otherwise.

Practical tools beyond formal canons

You rely on statutory structure to interpret individual provisions by examining how they fit within the broader legislative scheme. Cross-references between sections reveal connections that illuminate meaning, while defined terms sections establish precise meanings that control throughout the statute. Lawyers also consult legal dictionaries and treatises that explain how courts have historically interpreted similar language, building arguments on precedent rather than starting from scratch with each new case.

Using context, purpose, and history responsibly

You move beyond pure textualism when you incorporate legislative history, statutory purpose, and contextual evidence into your interpretation, but these tools carry risks alongside their benefits. Courts that rely too heavily on legislative history can substitute their policy preferences for statutory text, while ignoring context entirely produces mechanical readings that miss what drafters actually meant. Responsible legal interpretation requires you to use these supplementary sources carefully, treating them as aids to understanding ambiguous text rather than replacements for it. The challenge lies in drawing clear boundaries between legitimate contextual analysis and judicial overreach that rewrites laws under the guise of interpretation.

Legislative history as supplementary evidence

You consult legislative history to resolve genuine textual ambiguity after exhausting language canons and structural analysis. Committee reports, floor debates, and sponsor statements illuminate what problems legislators identified and what solutions they intended, helping you choose between plausible readings when text alone cannot decide. Courts examine legislative history to confirm that a proposed interpretation aligns with documented legislative intent, not to create meaning that contradicts clear statutory language.

Responsible use requires you to acknowledge that legislative history has limitations. Individual legislators may hold different views about what a bill accomplishes, and statements by single sponsors do not bind entire legislative bodies. You treat legislative history as evidence of collective intent only when multiple sources consistently point toward the same interpretation and when that reading remains faithful to enacted text.

Purposive interpretation without judicial activism

Your purposive analysis identifies the statute’s objectives by examining its structure, title, preamble, and relationship to other laws addressing similar subjects. You interpret individual provisions to advance these goals while respecting textual boundaries that limit how far purpose can stretch. When a statute aims to protect consumers from fraud, you read its requirements broadly enough to accomplish that protective function without extending coverage to conduct lawmakers never contemplated regulating.

Purpose guides interpretation within textual limits but never authorizes you to rewrite statutes to achieve results that language cannot reasonably support.

Judicial activism begins when you prioritize desired outcomes over textual constraints. Courts that invoke purpose to reach conclusions that statutory language directly contradicts have abandoned interpretation for legislation. You avoid this error by treating purpose as a tiebreaker between defensible readings rather than as authority to ignore text altogether.

Balancing text against external sources

You apply a hierarchy of interpretive materials that starts with statutory text and structure before moving to legislative history and purpose. When plain language answers your question, you stop there without searching for contrary evidence in committee reports. External sources become relevant only when text proves genuinely ambiguous after you have applied language canons and structural analysis to their limits. This disciplined approach prevents purpose or history from overwhelming the words legislators actually enacted into law.

Constitutional interpretation in plain English

Constitutional interpretation applies the same analytical frameworks you use for statutes but with higher stakes because constitutional text sits atop the legal hierarchy and changes rarely. You interpret the Constitution to determine whether government action falls within enumerated powers, whether laws violate individual rights, and how constitutional provisions apply to circumstances the Framers never imagined. Courts use distinct methodologies that reflect competing philosophies about where constitutional meaning resides and how judges should approach text written centuries ago. Understanding these approaches helps you predict how courts will resolve constitutional disputes and craft arguments that judges find persuasive in constitutional litigation.

Originalism seeks founding-era meaning

You apply originalist interpretation by determining what constitutional text meant to its ratifiers at the time of adoption. This approach requires historical research into how founding-era audiences understood specific words and phrases, relying on dictionaries, legal treatises, and contemporaneous documents from the 1780s. When you interpret the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on "unreasonable searches," originalists ask what searches and seizures the Framers considered unreasonable given 18th-century practices and expectations. This methodology constrains judicial discretion by tethering interpretation to historical meaning rather than evolving social values.

Originalism divides into two variants: original intent focuses on what the Framers subjectively meant to accomplish, while original public meaning asks how a reasonable person at ratification would have understood the text. You encounter this distinction when courts debate whether to examine Madison’s notes from the Constitutional Convention or whether to focus solely on how ordinary citizens would have read constitutional language.

Originalist interpretation treats the Constitution as law fixed at adoption, requiring amendment rather than judicial reinterpretation to adapt to modern circumstances.

Living constitutionalism embraces evolution

Living constitutionalists direct you to interpret constitutional text in light of contemporary values and circumstances, allowing meaning to evolve as society changes. This approach acknowledges that the Framers wrote in broad language precisely because they expected future generations to apply general principles to new situations. When you interpret "cruel and unusual punishment" under this framework, you examine current standards of decency rather than what colonists considered acceptable in 1791. Courts applying living constitutionalism have extended constitutional protections to technologies, social arrangements, and government practices unknown at founding.

You balance text against present-day realities under this methodology, reading constitutional provisions to remain relevant across centuries. Critics argue this approach gives judges too much power to impose their preferences, while defenders maintain it prevents the Constitution from becoming obsolete.

Practical hybrid approaches courts actually use

Most judges combine elements from multiple interpretive theories rather than adhering strictly to one methodology. You see courts begin with text, consult original meaning when historical evidence proves clear, consider structural relationships between constitutional provisions, and examine precedent that has shaped legal interpretation over decades. This pragmatic approach acknowledges that pure originalism sometimes produces unacceptable results while unfettered living constitutionalism lacks sufficient constraint. Judges weigh these factors case by case, making constitutional interpretation less predictable than statutory analysis but more adaptable to complex disputes involving fundamental rights.

Agency interpretations and deference after Chevron

Administrative agencies hold significant power to interpret the statutes and regulations they enforce, creating legal interpretations that affect millions of people and businesses daily. When the EPA reads environmental laws, when the SEC interprets securities regulations, or when immigration authorities apply visa requirements, they engage in legal interpretation that shapes compliance obligations and enforcement actions. For decades, courts deferred to reasonable agency interpretations under the Chevron doctrine, but the Supreme Court eliminated that framework in 2024, fundamentally changing how you evaluate agency legal positions and how courts review them.

How Chevron deference worked historically

Under Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, courts applied a two-step analysis when reviewing agency interpretations of statutes. You first determined whether Congress directly addressed the precise question at issue. If statutory language clearly resolved the dispute, courts enforced that plain meaning without deferring to the agency. When text proved genuinely ambiguous, you moved to step two and asked whether the agency’s interpretation was reasonable. Courts upheld any reasonable agency reading even if judges would have interpreted the statute differently, giving agencies broad latitude to fill gaps in legislative schemes.

This framework meant you often treated agency guidance documents, formal rulings, and regulatory preambles as highly persuasive authority because courts would likely defer to those positions. Attorneys counseling clients about regulatory compliance relied on agency interpretations as effectively binding law, knowing that challenges would succeed only if the agency acted unreasonably rather than incorrectly.

The Supreme Court’s reversal in 2024

The Supreme Court overruled Chevron in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, holding that courts must exercise independent judgment when interpreting statutes rather than deferring to agencies. The Court concluded that Chevron violated the Administrative Procedure Act’s command that courts, not agencies, decide all relevant questions of law. This shift returns interpretive authority to judges, requiring them to determine statutory meaning using traditional tools rather than accepting reasonable agency views.

Courts now interpret ambiguous statutes themselves rather than deferring to agency readings, placing judges back at the center of legal interpretation in administrative disputes.

What courts do now without Chevron

You approach agency interpretations today as persuasive but not binding authority. Courts still consider agency views, particularly when agencies offer technical expertise about complex regulatory schemes, but judges make independent determinations about statutory meaning using standard interpretive tools. Agency experience and specialized knowledge carry weight as contextual evidence, but courts no longer treat reasonable agency readings as dispositive when ambiguity exists. This change requires you to build stronger textual and structural arguments when defending agency positions, anticipating that courts will scrutinize legal interpretations more closely than they did under Chevron’s deferential framework.

How to interpret a legal text step by step

You approach legal interpretation as a disciplined process that moves through specific stages rather than jumping straight to conclusions. This systematic method prevents you from missing critical textual clues or imposing your preferred outcome onto ambiguous language. When you face a statute, contract provision, or regulatory requirement that requires interpretation, you follow a consistent framework that courts recognize and that produces defensible results. The steps below walk you through this process from initial reading to final conclusion, equipping you to analyze legal texts with the rigor judges and attorneys apply daily.

Start with the text itself

Your first step requires you to read the complete provision multiple times, paying attention to every word and punctuation mark. You identify defined terms, examine how clauses connect, and note the grammatical structure that shapes meaning. Legal drafters choose words deliberately, so you assume every term carries significance until proven otherwise. Look for internal definitions that control how the text uses specific language, because statutory or contractual definitions override ordinary dictionary meanings. You also examine titles, headings, and section numbers that provide context about how the provision fits within the larger document.

Identify where interpretation becomes necessary

After your initial reading, you pinpoint the specific ambiguity that requires interpretation. You cannot interpret effectively without first articulating exactly which words, phrases, or relationships create uncertainty. Does the text leave gaps about who qualifies under its terms? Does it use language susceptible to multiple reasonable meanings? You document these ambiguities precisely because legal interpretation addresses specific uncertainties rather than rewriting entire provisions.

You interpret only what the text leaves unclear, not what you wish it said differently.

Apply language canons and rules systematically

Once you have identified ambiguities, you apply interpretive canons methodically. You start with canons that govern textual relationships like expressio unius, noscitur a sociis, and ejusdem generis. These tools help you extract meaning from how words interact within the provision. Next, you apply any substantive canons that might control, such as the rule of lenity in criminal statutes or constitutional avoidance in provisions that might raise serious constitutional questions. Courts expect you to work through these canons rather than cherry-picking tools that support your desired outcome.

Examine surrounding provisions and context

You expand your analysis to examine how the disputed provision relates to neighboring sections, cross-references, and the overall statutory or contractual scheme. Provisions that appear ambiguous in isolation often become clear when you read them alongside related terms. Check whether other sections define key terms or establish principles that illuminate the disputed language. You also consider the document’s stated purpose if one exists, as preambles and purpose statements guide how you resolve textual ambiguities.

Consult precedent and authoritative materials

Your final step involves researching how courts have interpreted similar language in comparable contexts. You search for cases analyzing the same statute or regulatory provision, looking for binding precedent that resolves your interpretive question. When direct precedent does not exist, you examine decisions that applied analogous language in related legal areas. You also consult respected treatises and legal encyclopedias that synthesize how courts have approached similar interpretive challenges, building your analysis on established authority rather than inventing novel readings from whole cloth.

Next steps

You now possess the foundational framework that courts, attorneys, and legal professionals use to extract meaning from statutes, regulations, contracts, and constitutional provisions. The literal, golden, mischief, and purposive rules provide distinct pathways through ambiguous text, while interpretive canons offer systematic tools for resolving disputes about legal language. Applying these methodologies transforms you from someone who guesses at meaning to someone who constructs defensible legal arguments grounded in established principles.

Legal interpretation becomes particularly challenging when documents cross language barriers or involve parties from different legal systems. Accurate translation of contracts, court filings, and immigration documents requires professionals who understand both linguistic precision and legal context. When your matter involves multiple languages or requires certified translations that meet court standards, Languages Unlimited provides the expertise you need. Our team has spent over three decades helping legal professionals, courts, and government agencies navigate these complexities. Contact us to discuss how we support your specific legal translation and interpretation needs.