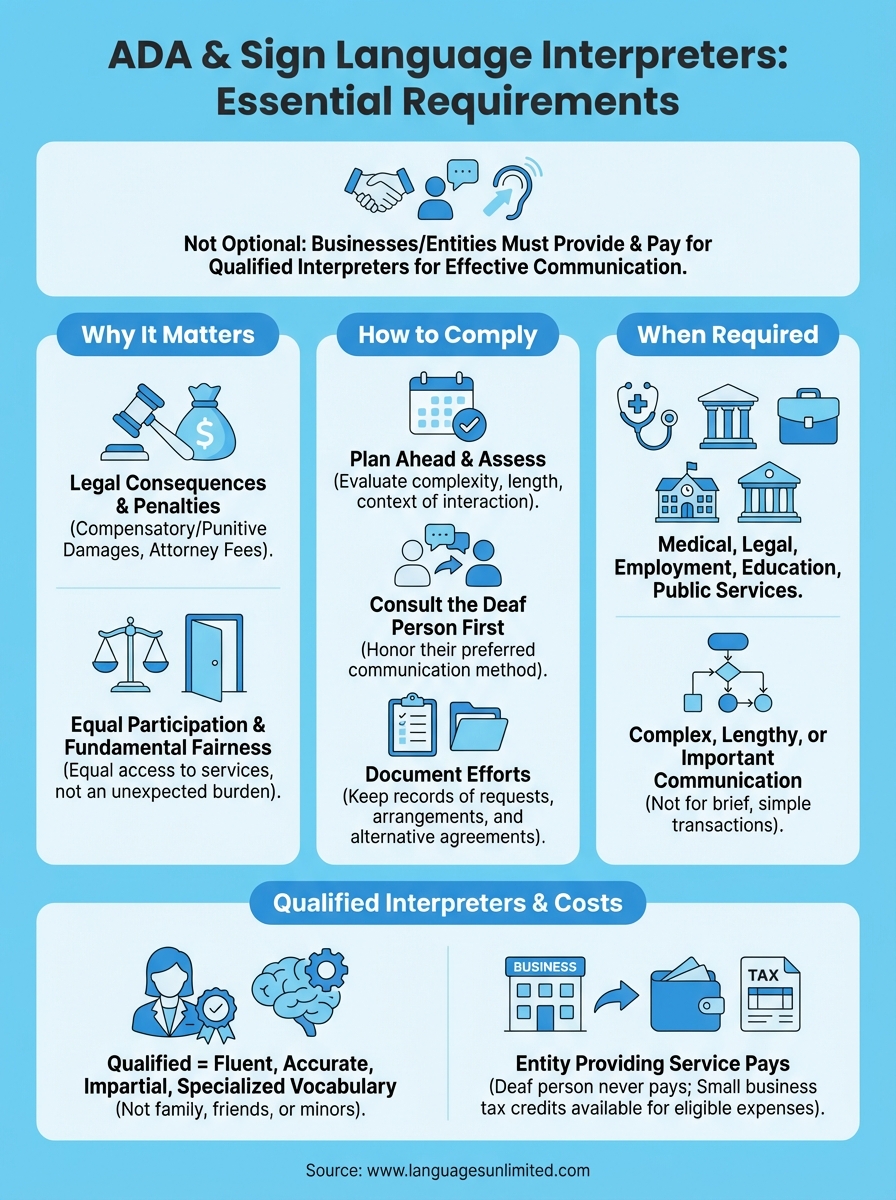

The Americans with Disabilities Act requires businesses and public entities to provide sign language interpreters when deaf or hard of hearing people need them to communicate effectively. This is not optional. Under federal law, you must arrange and pay for qualified interpreters in situations like medical appointments, legal proceedings, employment interviews, and many other interactions where clear communication matters. The rules apply to doctors’ offices, hospitals, courts, government agencies, schools, hotels, retail stores, and thousands of other locations open to the public.

This article breaks down exactly when you must provide an interpreter, what qualifies someone as competent under the law, and who shoulders the cost. You’ll learn which situations require an interpreter versus simpler alternatives, what the undue burden exception actually means, and how to plan and request services properly. We cover the compliance steps that protect you from discrimination claims while ensuring the deaf and hard of hearing community gets equal access to your services.

Why ADA interpreter rules matter

You face real legal consequences if you ignore ADA requirements for sign language interpreters. Courts have awarded hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages to deaf plaintiffs who were denied interpreters, and the Department of Justice actively investigates complaints. Beyond litigation risk, you violate federal civil rights law every time you refuse to provide effective communication for someone who is deaf or hard of hearing. The law treats communication access the same way it treats wheelchair ramps and accessible parking spaces. You cannot operate a public business or government service while excluding an entire population from meaningful participation.

Legal liability and financial penalties

Discrimination claims under the ADA carry compensatory damages, punitive damages, and attorney fees that quickly add up. A New Jersey jury awarded $400,000 to a deaf woman whose doctor repeatedly refused to provide an interpreter over an 18-month treatment period. Wal-Mart settled a case for $135,500 after denying interpreters during job interviews. These numbers reflect not just the denial itself but the ongoing harm caused when deaf individuals cannot participate fully in their own medical care, legal proceedings, or employment opportunities. Your insurance may not cover intentional discrimination, leaving you personally exposed.

Equal access protects everyone’s rights

The core purpose behind interpreter requirements is equal participation in society. When you communicate with hearing patients, customers, or employees without barriers, you must provide the same access to deaf individuals. A deaf parent deserves to understand their child’s medical diagnosis clearly, not through hastily scribbled notes or a nine-year-old family member. A deaf defendant needs to follow every word of testimony in their trial, not guess based on lip reading.

Effective communication ensures that deaf and hard of hearing people receive information as clearly as everyone else receives it.

Interpreter rules matter because fundamental fairness demands that disability cannot exclude people from healthcare, justice, employment, education, or public services. The law recognizes that spoken language creates an invisible wall for deaf people unless you remove it through qualified interpretation.

How to comply with ADA interpreter requirements

You comply with ada requirements for sign language interpreters by determining whether effective communication demands professional interpretation, consulting the deaf person about their preferred method, arranging qualified services promptly, and documenting your efforts. Compliance starts the moment someone contacts you about an appointment, service, or interaction. You cannot wait until they arrive to figure out how you will communicate. The law expects you to plan ahead and treat interpreter costs as a normal business expense, not an unexpected burden. Your obligation applies whether the deaf person is a patient, customer, employee, student, defendant, plaintiff, or member of the public accessing your services.

Assess each situation individually

Every interaction carries different communication demands, so you evaluate complexity, length, and context before deciding whether an interpreter is necessary. A brief retail transaction where a customer points to products and you ring up the sale rarely needs an interpreter. Written notes or gestures handle simple exchanges. A medical consultation about new symptoms, treatment options, or surgical procedures requires qualified interpretation because miscommunication can harm the patient. You assess whether the deaf person will understand critical information and whether you will understand their questions or concerns clearly through alternative methods.

The nature of the conversation determines your obligation. Legal proceedings, employment terminations, financial counseling, mental health therapy, and complex technical discussions almost always require interpreters. Routine follow-up appointments, basic transactions, or simple scheduling questions may work through writing or other auxiliary aids. You make this determination based on what the specific situation demands, not based on what costs less or feels more convenient for your staff.

Consult with the deaf person first

You ask the deaf individual which communication method works best for them before deciding on your own. Some deaf people prefer American Sign Language interpreters, while others use signed English or rely on assistive listening devices if they have residual hearing. Many deaf individuals communicate perfectly well in writing for certain contexts but need interpreters for detailed discussions. You honor their stated preference unless you can demonstrate that another equally effective method exists and the person agrees it works.

The deaf person knows their own communication needs better than you do.

Family members, friends, and children should not serve as interpreters except in genuine emergencies. Professional objectivity matters because relatives may have emotional involvement, may lack vocabulary for technical subjects, and cannot maintain confidentiality. A nine-year-old child should never interpret their parent’s medical diagnosis or legal problems. You find a qualified professional interpreter instead of relying on whoever happens to be present.

Document your compliance efforts

You keep records of every request for interpreters and how you responded. Write down when someone asked for services, what you arranged, when the interpreter arrived, and how long they stayed. Documentation proves you took reasonable steps to provide effective communication if someone later files a complaint. Records also help you identify patterns, such as which departments need interpreter services most often or which language combinations you request frequently.

Your documentation should include any alternative arrangements the deaf person agreed to accept. If they consented to video remote interpreting instead of on-site services, note that agreement in writing. If they preferred written communication for a simple interaction, record that preference. This paper trail demonstrates you evaluated each situation individually and worked collaboratively with the deaf person to ensure effective communication through the most appropriate method available.

Who must provide and pay for interpreters

The entity providing the service or program pays for the interpreter, not the deaf person. If you operate a hospital, law office, retail store, hotel, government office, or any other public accommodation, you absorb the cost as part of your obligation to provide equal access. The ADA treats interpreter fees the same way it treats building entrance ramps or accessible parking spaces. You cannot pass this expense to the person with a disability or add surcharges to their bill because they need communication access. Your standard pricing applies regardless of whether someone requires an interpreter to use your services.

Businesses and public accommodations

Any private business open to the public must provide and pay for interpreters when effective communication requires them. This includes medical offices, dental clinics, pharmacies, banks, insurance companies, retail stores, restaurants, hotels, theaters, gyms, and professional services like accounting or legal firms. The size of your business does not eliminate the obligation, though smaller operations may qualify for limited exemptions under the undue burden standard. You budget for interpreter costs as an operational expense because ada requirements for sign language interpreters apply whether you serve five customers per day or five hundred.

Healthcare providers face particularly strict obligations because medical communication directly affects patient safety and outcomes. A doctor who refuses to provide an interpreter and relies on family members or hastily written notes violates federal law, even if the medical treatment itself proves adequate. Courts have ruled that effective communication is separate from quality of care. You can deliver excellent medical outcomes while still discriminating if the patient could not fully participate in treatment decisions or understand critical information about their condition.

Government agencies and public entities

State and local government offices, courts, police departments, public schools, public universities, and municipal services must provide interpreters under Title II of the ADA. This includes everything from DMV appointments to city council meetings, court proceedings to public hearings. Government entities face even fewer exceptions than private businesses because taxpayer-funded services must remain accessible to all citizens. Public schools provide interpreters for parent-teacher conferences, IEP meetings, and school events open to families, not just for deaf students during instruction.

Law enforcement agencies must provide interpreters during arrests, investigations, and interrogations. A deaf suspect has the right to understand their Miranda rights and communicate with officers through qualified interpretation. Courts provide interpreters for deaf defendants, witnesses, and family members attending proceedings. These constitutional rights to due process and effective legal representation demand professional interpretation, not amateur efforts by jail staff or relatives.

The deaf person never pays

You cannot charge deaf individuals for interpreter services, directly or indirectly. This means you cannot add a fee to their invoice, require a deposit, or increase your standard rates to offset interpreter costs. Small businesses with legitimate undue burden claims might negotiate alternative effective communication methods with the deaf person, but you never shift the financial burden to them. Tax credits exist for small businesses to help cover accessibility expenses, including interpreter fees, so you explore these options rather than passing costs to customers or patients who need communication access.

When a sign language interpreter is legally required

You must provide a sign language interpreter whenever the complexity, length, or importance of the communication makes simpler methods inadequate for effective understanding. The law does not set rigid rules listing every situation that requires interpretation. Instead, ada requirements for sign language interpreters focus on the functional outcome: can the deaf person receive information and communicate back with the same clarity and detail that a hearing person would experience? If written notes, gestures, or assistive listening devices cannot achieve that standard, you provide a qualified interpreter.

Medical appointments and healthcare settings

Hospitals, clinics, and private medical offices must provide interpreters for most patient interactions beyond basic scheduling or vital sign checks. A routine blood pressure screening may work with written communication or simple gestures because the exchange involves minimal information. Diagnosing symptoms, explaining treatment options, obtaining informed consent for procedures, discussing test results, and mental health counseling all require professional interpretation. You cannot rely on family members to interpret sensitive medical information, and you cannot expect patients to make health decisions based on incomplete understanding through lip reading or hastily scribbled notes.

Emergency room visits require interpreters even when time pressures exist. You arrange for video remote interpreting if an on-site interpreter cannot arrive immediately, but you do not skip interpretation because the situation feels urgent. Medical decisions made without clear communication violate federal law regardless of whether the clinical outcome proves satisfactory.

Effective communication in healthcare is a separate legal requirement from the quality of medical treatment itself.

Legal and employment contexts

Courts provide interpreters for all proceedings involving deaf defendants, witnesses, plaintiffs, or family members in the courtroom. Police departments arrange interpretation during arrests, interrogations, and suspect interviews. Constitutional due process demands that deaf individuals understand charges against them and participate fully in their defense. Lawyers provide interpreters during client consultations, depositions, and contract negotiations because legal communication carries serious consequences when misunderstood.

Employment situations require interpreters during job interviews, performance reviews, disciplinary meetings, safety training, and workplace investigations. A deaf employee has the right to understand personnel policies, participate in staff meetings, and receive the same information hearing employees get. Simple daily work instructions might happen through email or messaging apps, but any complex discussion about job duties, benefits, or workplace issues needs qualified interpretation.

Educational programs and public services

Schools arrange interpreters for parent-teacher conferences, IEP meetings, school board hearings, and public events even if the deaf student already has an educational interpreter during class. Government agencies provide interpretation for public hearings, municipal services, and benefit applications. Hotels offer interpreters for conferences and events they host when requested with reasonable notice. The determining factor remains whether the deaf person can participate meaningfully in the activity or service without professional interpretation.

Short interactions like purchasing retail items, ordering food at a restaurant, or checking into a hotel rarely need interpreters because the transaction involves limited information exchange. You would need interpretation if the customer asks detailed questions about product specifications, dietary restrictions, or hotel amenities that cannot be answered clearly through writing. The situation dictates the requirement, not arbitrary rules about which industries or settings always require interpreters versus those that never do.

What makes someone a qualified sign language interpreter

A qualified sign language interpreter can interpret effectively, accurately, and impartially in both directions using any necessary specialized vocabulary for the context. The ADA does not require certification as the sole measure of qualification, though state laws may impose stricter standards that supersede federal requirements. You determine whether an interpreter qualifies based on their ability to handle the specific communication situation at hand, not by checking a credential alone. An interpreter certified by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf might lack expertise in medical terminology if your situation involves complex healthcare discussions, while an uncertified interpreter with extensive medical experience could meet the qualified standard for that context.

Professional competence and certification standards

Certification through organizations like the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf provides strong evidence that someone meets professional standards, but the ADA definition focuses on functional ability rather than credentials. You verify that the interpreter demonstrates fluency in both sign language and spoken English, understands the subject matter vocabulary, and can interpret accurately without adding, omitting, or altering meaning. Different certification levels exist for legal, medical, and educational settings, so you match the interpreter’s qualifications to your specific needs.

State licensing laws often require certified interpreters for certain situations, particularly in court proceedings or government services. You check local requirements because state law can establish higher standards than federal ADA minimums. When state law mandates certification, you must comply with that stricter requirement regardless of whether the federal standard would accept someone without credentials.

Language proficiency across systems

Qualified interpreters demonstrate fluency in the specific sign language system the deaf person uses. American Sign Language and signed English represent different systems with distinct grammar and syntax. An interpreter proficient in ASL may struggle with someone who uses signed English or another variant. You confirm the interpreter and deaf person share a common language system before assuming communication will work effectively.

The most credentialed interpreter in your city still fails the qualified standard if they cannot communicate in the deaf person’s preferred sign language system.

Technical situations demand interpreters with specialized vocabulary knowledge. Medical interpreters need anatomical terms and drug names. Legal interpreters must understand courtroom procedures and legal concepts. Educational interpreters should know academic subject matter. You evaluate whether the interpreter’s expertise matches the complexity of the discussion rather than assuming any sign language interpreter works for all contexts.

Impartiality and professional boundaries

Family members, friends, and minor children cannot serve as qualified interpreters except during genuine emergencies when no alternative exists. These relationships create conflicts of interest that compromise accurate interpretation. A daughter interpreting her mother’s cancer diagnosis faces emotional involvement that affects objectivity. Children lack the maturity and vocabulary for adult situations. Friends may filter information they consider upsetting rather than interpreting exactly what the provider says.

Professional interpreters maintain confidentiality and neutrality that relatives cannot provide. They interpret every word without censoring, summarizing, or editorializing. The ada requirements for sign language interpreters specifically address this issue by defining qualification partly through the interpreter’s ability to remain impartial. You arrange professional services rather than relying on whoever accompanies the deaf person to avoid ethical violations and ensure truly effective communication.

Alternatives to interpreters and when they work

The ada requirements for sign language interpreters recognize that simpler communication methods work effectively in many situations, so you explore alternatives before automatically hiring a professional interpreter for every interaction. You consider written notes, real-time text messaging, assistive listening devices, and video remote interpreting as potential options depending on the context and complexity of the exchange. The key test remains whether the deaf person receives and conveys information with the same clarity a hearing person would experience through standard spoken communication. Alternative methods satisfy legal requirements only when both parties achieve genuine understanding.

Written communication and note exchange

Exchanging handwritten notes or typed messages works well for brief, straightforward transactions that involve limited information. Scheduling appointments, confirming addresses, processing simple retail purchases, and answering basic yes-or-no questions usually succeed through writing. You verify that the deaf person reads and writes English fluently before relying on this method because written English proficiency varies widely among deaf individuals who use sign language as their primary language. Many deaf people find writing adequate for quick exchanges but frustrating for detailed discussions that require back-and-forth conversation.

Written communication becomes inadequate when the topic involves technical vocabulary, complex instructions, or emotional content that demands nuanced expression.

Medical offices cannot obtain informed consent for surgery through hastily scribbled notes. Employment terminations require more than a written explanation handed to someone being fired. Legal consultations demand the ability to ask clarifying questions and receive detailed answers that writing alone cannot provide efficiently. You assess whether the alternative method gives the deaf person equal participation rather than settling for minimal understanding.

Video remote interpreting and assistive technology

Video remote interpreting connects you with qualified interpreters through videoconferencing platforms when on-site interpreters cannot arrive quickly enough. This technology works particularly well in urgent situations like emergency room visits or unexpected legal proceedings where you need immediate access to interpretation services. You ensure stable internet connections and appropriate display screens so both parties can see the interpreter clearly. Assistive listening devices help people with residual hearing by amplifying sound, though these devices serve hard of hearing individuals better than profoundly deaf people who rely on visual communication.

Undue burden, exemptions, and small business relief

The ADA recognizes that requiring interpreter services could create significant difficulty or expense for some entities, so the law includes an undue burden exception that might excuse you from providing an interpreter in specific circumstances. This exception applies narrowly and requires careful documentation because courts scrutinize undue burden claims closely. You cannot simply claim financial hardship and refuse services. Instead, you must demonstrate that providing an interpreter would fundamentally alter your operations or impose unreasonable costs relative to your resources. The burden of proof rests entirely on you to show why this particular situation exceeds what the law considers reasonable accommodation.

What qualifies as an undue burden

You establish undue burden by examining the nature and cost of the accommodation against your overall financial resources, not just the cost of one interpreter visit. Courts consider your total budget, the resources available at the specific location providing services, and whether you operate as part of a larger organization with shared finances. A solo medical practice with three employees faces different expectations than a hospital system with millions in annual revenue. The evaluation includes whether you could reasonably absorb interpreter costs through existing budgets, insurance reimbursements, or operational adjustments.

Temporary financial difficulties rarely justify undue burden claims because the law expects you to plan for accessibility expenses as part of standard operations. You cannot argue that interpreter fees create hardship simply because you did not budget for them or because they exceed the revenue from serving one deaf customer. Courts look at your organization’s overall financial health, not whether a single transaction proves profitable after paying for interpretation services.

Small business tax credits and financial relief

Small businesses with 30 or fewer employees or $1 million or less in gross receipts qualify for the Disabled Access Credit, which covers 50 percent of eligible expenses between $250 and $10,250 annually. This tax credit reduces your actual cost of providing interpreters and other accessibility accommodations substantially. You claim this credit on IRS Form 8826 when filing your federal tax return. The credit applies to various disability access expenses, including interpreter services, assistive technology, and accessibility modifications.

The federal tax code provides financial relief specifically to help small businesses comply with ada requirements for sign language interpreters without devastating their budgets.

You explore these tax benefits before claiming interpreter costs create undue burden because the relief programs exist precisely to make compliance affordable for smaller operations. Many small businesses discover that after applying available tax credits, the net cost of occasional interpreter services becomes manageable within normal business expenses.

How to document a legitimate burden claim

You gather detailed financial records showing your total operating budget, revenue, and expenses if you believe providing an interpreter creates genuine hardship. Documentation includes profit and loss statements, tax returns, employee payroll records, and analysis of what percentage of your budget the interpreter cost represents. Courts examine whether you explored alternative funding sources like grants, tax credits, or payment plans with interpreter agencies before refusing services.

Your documentation must prove you considered less expensive alternatives that still achieve effective communication, such as video remote interpreting instead of on-site services. You cannot claim undue burden without demonstrating you investigated all reasonable options and found none financially feasible given your specific circumstances.

Practical steps for planning and requesting interpreters

You plan for interpreter services by contacting qualified providers as soon as you know a deaf person needs your services, typically several days to weeks in advance for routine appointments. The ada requirements for sign language interpreters emphasize effective communication, which begins with giving yourself enough time to secure appropriate services rather than scrambling at the last minute. You build interpreter requests into your standard intake process for new clients or patients, asking about communication needs during initial contact the same way you ask about insurance information or appointment preferences. This proactive approach prevents delays and ensures you fulfill legal obligations without disrupting your operations.

Contact interpreter agencies early

You reach agencies at least three to five business days before scheduled appointments for routine situations, though urgent needs may require same-day video remote services. Many qualified interpreters maintain full schedules, particularly for specialized assignments like medical or legal work. Early contact gives agencies time to match you with someone who has appropriate expertise and availability for your specific situation. You maintain relationships with multiple interpreter services to ensure backup options exist when your primary agency cannot fulfill a request.

Finding interpreters becomes easier when you use established referral sources like the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, your state office for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, or local chapters of the National Association of the Deaf. These organizations maintain databases of qualified professionals in your area. You ask the deaf person whether they have preferred interpreters they work with regularly, as this often produces faster results and better communication outcomes.

Provide detailed situation information

You tell the interpreter agency the date, time, and expected duration of the appointment, along with specific details about what will be discussed. Medical offices share the type of appointment, whether it involves diagnosis, treatment planning, or routine follow-up. Legal practices explain whether the session involves contract review, litigation strategy, or client intake. This information helps agencies assign interpreters with appropriate specialization and prevents mismatches where the interpreter lacks necessary vocabulary or context.

Location details matter because interpreters need clear directions, parking information, and instructions for checking in at your facility. You include the deaf person’s preferred sign language system and any special needs like low vision that might affect positioning in the room.

The more specific information you provide upfront, the better the agency can match you with a truly qualified interpreter who makes the session productive.

Confirm arrangements in writing

You document all interpreter bookings through email confirmation that includes the date, time, location, assigned interpreter’s name, and agreed-upon fees. Written records protect both parties if disputes arise later about whether services were requested or confirmed. Your confirmation should specify the cancellation policy and minimum booking time, as most agencies charge for the full contracted period regardless of whether your appointment runs shorter than expected.

Prepare your staff and space

You brief your team that an interpreter will attend the appointment so front desk staff know to check them in properly and maintain confidentiality. The interpreter sits or stands where the deaf person can see them clearly while also maintaining sight lines to you. You arrange furniture to create a triangular seating arrangement that allows comfortable visual access for everyone. Adequate lighting matters because sign language depends on clear visibility, so you avoid positioning interpreters in front of bright windows or in dimly lit corners that make signs difficult to see.

Key takeaways on ADA interpreters

The ada requirements for sign language interpreters demand that you provide qualified professionals whenever effective communication requires them, with you paying the cost rather than passing it to deaf individuals. You evaluate each situation based on complexity, length, and context to determine whether an interpreter is necessary or whether simpler alternatives like written notes achieve genuine understanding. Qualified interpreters demonstrate fluency in the deaf person’s preferred sign language system, possess specialized vocabulary for your context, and maintain professional impartiality that family members cannot provide.

Small businesses can access tax credits to offset interpreter expenses, though undue burden claims require detailed financial documentation proving genuine hardship rather than mere inconvenience. You plan ahead by contacting interpreter agencies several days in advance, providing specific details about the appointment, and preparing your physical space for effective visual communication. Non-compliance risks substantial damages, federal investigations, and exclusion of deaf people from equal participation in your services.

Contact our team to arrange qualified sign language interpreters for your business and ensure full ADA compliance.